An accounting of the visible world and the invisible world: this is one definition of art that Richard Tuttle has offered up over the course of his five-decade career. With two major presentations of the American artist’s work currently on view in London – a career-spanning survey at the Whitechapel Gallery (through December 14) and a massive wood- and textile-based sculpture filling Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall (through April 6) – these words perhaps offer a key to accessing the depth of Tuttle’s oeuvre, one that can range from arresting and voluminous (as is the case at the Tate) to so slight in appearance that the objects can barely be perceived at all (as several examples at the Whitechapel attest.) Whereas an orthodox Minimalist would take pains to enunciate nothing beyond the blunt physicality, the isness of an exhibited object, Tuttle’s objects, be they flat or three-dimensional, are allusive devices in an open machinery of poetics, rather than contributors to a neo-formalist discourse on flatness. The nether region between the visible and the invisible is the same realm occupied by poetry, and the significant inclusion of Tuttle’s own poetic texts, accompanying each of the exhibited objects at Whitechapel, further exemplifies the artist’s straddling, not only of two different worlds, but of two different languages: the linguistic and the visual. Far from illustrating or commenting on the works they accompany, Tuttle’s object-oriented texts posit a parallel practice, a hidden simultaneity that defies his objects’ staticity, instead grounding them in a metaphysical continuous present.

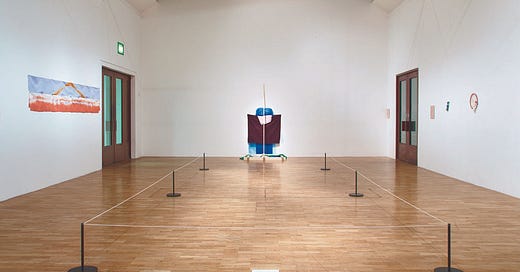

There is a pervasive delicacy, a fragility, an exposed vulnerability that is characteristic of the forms Tuttle makes. A good example of this can be found in “Looking for the Map 8,” 2013–14, installed on the upper floor of the Whitechapel exhibition. The piece looks like it could collapse at any moment. Three narrow wooden boards turned at a precarious upright angle and placed atop two others form a foundational plinth. A long cylindrical slab of wood bisects the piece, resting, again precariously, against the wall above, liable to fall apart would someone even breathe on it. The work concludes with a draping of richly saturated textiles – blue and green cloths and tulle, as well as a section of striped, deep magenta suit-like material painted with a concentrated circle of soft pink.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Travis Jeppesen to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.